My place in the tundra came to exist one summer of longing and desperation, one moment when my children were three and eight years old. In a heart so full as a motherís can be, of love and daily care for her kids, there may not be conscious reflection on how much she is, in fact, not doing.

I was stuck in Houston. I perceived myself to be stuck in a relationship, with young sons and no way to independently support myself and them. I telephoned my ex-boyfriend, "Tundra Tom" Faess, who had stayed a good friend well after our own tempestuous romance had imploded and even after I took up with the father of my youngest, in whose care both boys were to remain for the next three weeks. Tom said that if I could get to Yellowknife, Iíd be home free. He would take me out to his basecamp on Whitefish Lake, near the edge of the Thelon Game Sanctuary.

I flew to Yellowknife, capital of the vast Northwest Territories, little-known to the outside world, but tremendously dynamic in its combination of small size, governmental, tribal and industrial importance, and location amidst wilderness. Real wilderness, or pretty near. I remember the flight from Houston, looking down on the irritating regularity of farmland (all the way from Texas to Alberta), the land harnessed and tamed, natural areas relegated to the margins. Then somewhere beyond Calgary came forests... and also highways. Presently, I saw fewer roads, but then there were exploration marks, straight lines slicing the tree carpet. But these, too, disappeared. Just forest and rock and water slowly passed below the jet.

The approach to Yellowknife brought us down, down, the rocks closer and closer and faster and faster, the granite just under the surface of the western arm of Great Slave Lake appearing green and then gold in a realm of turquoise blue.

We landed. We walked across the tarmac the old-fashioned way and there was Tom. Reuniting was happy after all those years, but my excitement magnified when we loaded gear and ourselves into the red Beaver, a float plane considered the work horse of the Arctic. I considered it the Ď56 Chevy of the skies (in sound, size, and shape), and indeed, the Beavers are from that era, still trucking their loads of fuel, goods and people where cars cannot go.

I had not flown in any kind of small plane previously, and was as blown away as a kid on coffee. The spray flew back from the riveted metal pontoon floats in a mint-green shower and with a roar we disconnected from the surface of the earth. We were a noisy juggernaut, spiraling up around the city in the golden sun of the afternoon, all mosquitoes left behind. You canít hear anything else in those planes except with ear phones, so conversation that couldnít match the beauty of the land was moot.

The thing about that wild land, the tundra, is that it is half covered with water. Little lakes with ruffled surface, larger lakes and streams and especially tiny lakes glistened everywhere, cradled by the permafrost just feet below the brush. For millennia, the same water froze and thawed every year and never flowed away.

We sped (chugged) low over a brown and gold carpet, spotted by ancient, weathered, gray rock. No roads, no straight lines, just the meanderings of caribou paths, converging at a water crossing and fanning out again. The window was wide open. I was still amazed, hanging my head out of a flying airplane, feeling the sharp, cool air.

The basecamp was cute...comfortable...and QUIET after we landed and the Beaver engine sputtered to a stop, with the plane floating silently across the last forty feet to the sandy shore. Time to jump out ósomebody has to get their feet wet and pull the aircraft by a rope far enough onto the beach so tourists and southerners can gingerly step onto the float, walk its length hanging on to the struts and hop to dry land. We set up, were shown to tents, marveled at the hot shower, ate comfort food and generally settled in.

My epiphany came the next day. Tom told me to go out alone. That will make or break a person, being confronted, as it were, with only themselves and the earth. And thatís when I fell in love.

I maybe didnít even know it; I maybe didnít even know anything. What I found, out there in the sighing quiet, in the place where things are not named or constrained, where there is not one single person other than our party within hundreds of miles, where there is not a fence or a vehicle driven by an ďownerĒ, what I found was that the layers of care and worry that arise within us as we carry out all our roles in everyday life fell away, like tears and like rain. Out there, any tears that I might cry were just as good as rain. And all is received. The land holds you in its hand and lets you express everything that needs to find a way out.

It also fully receives your love. Over the next hours and days I saw how avenues in my life were restricted, how the burden side of kids and meals and never enough time was a weight heavier than I wanted to think about in the blush of love for my babies, my growing children. And I saw that it was time to leave my relationship, that his claim to the greatest possible adoration was not necessarily incorrect from his point of view, but amounted to emotional blackmail, even if unintentional.

I felt how much I loved the wordless land, this place that later came to have a spiritual face. I felt the flood of RELIEF at not being hemmed in by malls and power lines and too many people.

The gentle, intense colors of the tundra flora enchanted my artistís vision. We were instructed not to wear bright, unnatural colors, as these might alarm wildlife, and I was glad. It was not the time to bombard my eyes with chemically dyed day-glo nylon, or the like. Now, when I followed a path through esker pines and came on a patch of lightest green lichen, my eyes were ready to drink up this luminous bed of sky beneath my feet. And just as vision begins to open, so does the soul, with a sense of possibility. This is simply because of the lack of trees, or rather, the SIZE of the trees that do grow on the tundra, far beyond the tree line, such as the knee-high willows. The uninitiated might have called them shrubs.

This openness, such that your eye travels as far as it possibly can, in ALL directions, gives a breath-taking impression of freedom--physical and psychological. Trees are beautiful and there is nothing like the majestic, gigantic redwoods of my California home, but no trees obstructing your view is also an incredible thing. You can see. You donít have to be spooked by something around the corner. Itís hard for anything to LURK in the tundra.

Not that it canít happen. I heard about the mythical ill spirit called Tongak, that roams and can freak out dogs as well as humans. I was not of any mind to doubt the stories, but felt something like a yawning malevolence only once, in a man-made place. This occurred one afternoon, maybe 5 PM, after a tense hair-cut session, in which I was supposed to administer a little trim... You know, it's easy. But Tom, being the recipient of the cut and now a SHAVE as well, seemed to expect the result to be more and more smooth and conservative. Helmet-hair isn't within my scope, nor in this case was it even a possibility, as you would know if you knew Tom, and my inspiration was evaporating. I think my trip to the bath house had something to do with the razor, which maybe affected my psyche, but I can tell you that what I felt in the back of the building, by the showers, was pure menace. To this day, I have no explanation of it.

The land, as it presented itself to me, though, was deeply sweet. Every berry is edible, including the amazing cloudberry, that lightens as it ripens. There are no venemous creatures, nor even any snakes at all. The sun in summer stays up so long that night is like twilight and sometimes a silent fog rolls in to deepen the silence that soothes your weary city ears.

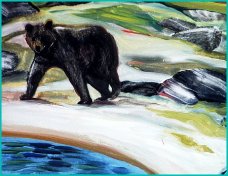

This is not to be ignorant of risk. Bears awe and scare me. If I encounter one I will only be able to have lived the best life I can, and sing a song to it, a song I hope may be interesting enough for its curiosity to spare the mother of my children.

And there is always winter to think about. The honey kiss of the summer tundra is the flip side of a winter freeze so deep we canít know it, we who havenít lived in it, who havenít felt what 60 degrees below zero Fahrenheit means, if only to your lungs and nose. The midnight sun of midsummer gives a lot of extra energy to people, as well as a touch of madness. I can only imagine what hardship, as well as possible hidden benefits, months of winter darkness would provoke.

Towards the end of two weeks at camp, I remembered I had children. And responsibilities. We had not spoken once--there were no normal telephone lines and the satellite phone was used just for emergencies. A low cloud cover rolled in. Nothing seemed severe, but conditions were not flyable. My airline ticket return date passed. We ate pancakes for breakfast, planned a berry pie, and I didnít care. I was in a tundra trance, and boy did I need it. Nothing mattered, only the earth , the sky and the frigid water I waded through naked on upturned shards of shale, to get to the northern area, the final direction of my solitary exploration.

Do you need to go so far to find peace?

Maybe sometimes you do. And I did. I found peace and a place that answered what I had always felt at the solid center of my heart. I felt like my head was emptying out and would only take in what I could taste and feel and see. What filled my head was the sound of the wolf calling, and the sight of its white form floating over the silver moon path in the midnight twilight. So far away could I see, yet it seemed so close. When I lay dreaming on their lookout hill near the den, feeling my body sink inside the earth that was red behind shut eyes, I fell in love.

That place that harbors nothing ugly got my heart. Even the scat there is clean; that of the wolf is made of fur and bone, turns white and does not smell. No place or creature is perfect, but our allegiance must lie somewhere on this earth and that part of the Canadian tundra surrounding the Thelon River woke me up.

Forgive me for falling asleep in my life, but I woke up. Because I woke up, I went back to Houston with the inspiration to make drastic changes and to achieve not just an adventurous escape for myself, but a new life for the kids, too, for all of us together.

Change doesnít always happen one-hundred percent or immediately, and I returned to the Thelon first. Tom had the idea for a mural on the building that housed his business, Great Canadian Ecoventures. The location was a historic structure in the Old Town part of Yellowknife. Whatís more, the building faces the small causeway that leads to Latham Island, where quite a few wealthier Yellowknifers live and where a Native community is situated. Any mural here would be seen daily by many.

|

I came north again, and painted the Thelon mural for Tom, for the town, for the land that I loved, for free. Tom flew me up, took care of me there, and flew me out to the camp again. Again, tears of joy.

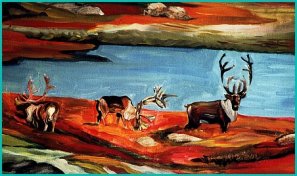

The mural took shape as a fantasy landscape depicting the tundra during the day, at sunset, and at night under the aurora borealis. It moves from Spring to Summer to Fall and includes classically recognizable arctic animals, such as the musk-ox, caribou, and white wolf. It was painted in exterior latex house paint on primed ply-wood panels and measures 20x16 ft. The mural was very well received and I am forever grateful to the people of the city of Yellowknife for their response to me. I wanted to stay and would have if I had had my kids with me.

|

|

But my inspiration for leaving Houston after twenty years, two advanced degrees, and about a million parties was firm. I still felt stuck, but much less so. I loved the beautiful, balmy summer nights, the soft spring breeze bringing humidity from the Gulf of Mexico, the sweetness of the rocky Texas Hill Country, and my friends from Rice University, the Houston Heights, and the Council of the Magickal Arts with whom Iíd shared so much. However, those connections never really die and for my life I had to go.

A girlfriendís brother sold me a 1977 International Harvester school bus that came from Alaska (twice) and my beloved friend Melanie told me to find my way to Northern California. On July 9, 1999, the bus was loaded down and we were loaded up for the big search. As the kids and a friend and I rode those crowded freeways out of town one more time, I tasted freedom. The freedom of the open road and pretty nice it was.

We visited my folks and dear friends in Wisconsin, crossed the wide Mississippi at Prairie du Chien, rolled over so many miles of farmland and then.... passed from farm to range land. Again that feeling of relief, of seeing the land less bound. I am my Irish great-grandfatherís descendant in heart as well as in blood. He traveled out west and wanted nothing more than to live with the Plains Indians and their horses. Horses and Indians and wolves and dolphins have been my spirit companions since childhood, when my sisters and I dressed our Barbies in leather and fur and had them ride poseable horses. The cowgirl doll, Jane, in her molded blue plastic clothes, was neglected. Our Mom made us a teepee and we (at least I) just wanted to run wild. ďIíll never get married! Iíll never be normal...Ē

Not everything you say fervently comes true, but it usually has a seed of truth. My great-grandpa didnít stay with the Indians; he got married and went back to Michigan. I did get married (at eighteen!), but never was ďnormalĒ. And now I felt GOOD trucking into the dry, open, beautiful foothills with my boys.

The apparition of the Rocky Mountains was thrilling and by the time we got to the Grand Canyon, my brain was almost able to wrap itself around the sacred immensity I was seeing. The tundra was so scaled to me... the Grand Canyon was scaled to the gods. I was really scared there, trying to rein in my headstrong niece and hardly more tractable boys. Those drop-offs are as real as they are big and it was pointed out in the Visitor's Center that people meet tragedy every year here. Ninety-nine percent of the time, I am unflappable, and as a mother, not over protective, but what breathtaking largeness lay before me and where were those kids now?? In the end, they flopped down on the beds in the bus and I took a last sunset drink through my eyes of that chasm and felt exaltation.

We passed through piney New Mexico and the red rock of Arizona. Then California! And it was not easy eating all fifteen apples and several mangoes because we forgot during the last grocery stop about this stateís strict agricultural checkpoint . At least it was hot.

It got really hot in the Mojave Desert and had that barrenness so dear to my heart. Then suddenly, there was Los Angeles, into which we were dumped flying through those desert mountains. Los Angeles was the land of flowers to me, and it only got better. The geography and vegetation of the California coast were entrancing, but it was also here in Los Angeles that I first saw, then felt and tasted the second giant of my trip, the biggest giant, the giant that is now a part of my life, the Pacific Ocean.

Big Sur had the most surpassing beauty, but where to live? Where was our place? By this time, I was ready to find it or be found by it. Santa Barbara was even more drenched in flowers, but we kept not finding it, we kept getting back in the bus, getting back to the road and driving further on.

The first thing we did in San Francisco was sleep a half night in the parking lot of a nation-wide greasy spoon chain so that my 13-year-old niece Samantha, who'd joined us in Wisconsin, could be delivered to the airport at 6 AM in her own personal coach. Admittedly, the ride was a little rough, but we arrived, on time, and neither crashed nor became wedged between the pavement and a low ceiling. All the bitterness my companion was slinging in my direction was really not helpful and he ate his words two days later. But first, the Bay area provided a nice rest stop at the house of a dear college friend, now a wedding photographer, who has a vast knowledge concerning wine and gracious dining, having been a high-end waiter for years. He stayed in it for the money for a long time, but now was the waitee not the waiter. I was grateful to be wined and dined in this manner for three hours on an afternoon while the guys shopped.

In Bolinas, which was fabulous, except that its reputation was twenty years old and it no longer contained any reasonable place to rent, our group of four was reduced to three, and necessity dictated that I learn to drive the bus. I received a parking ticket for vehicular habitation, which sounds either lewd, red-neck or both, and my companion went to jail. The reason was gross bureaucratic mismanagement on his part of some old, forgotten traffic citations. The result was harsh for him and disturbing for the boys, but the officer involved was absolutely courteous and helped make sure I was capable of proceeding out of town without hitting a building. Naturally, I perceived that it would have been smart to have learned to navigate my own ship and not to have let someone else do all the driving because he already knew how. It was a sudden lesson, but it worked. I remember sliding by the eucalyptus giants, psychically floating through hair-pin turns in those grassy Marin County hills. It was almost dusk and I was getting the hang of it, but I really needed to get wherever it was that we were going. The kids were shaken and I still had to figure out the propane tank.

The boys and I reconnoitered at Dillon Beach for a week. I have always been independent and these days of regrouping were a relief. I continued painting murals on the sides of the bus to advertise my artwork and to make it easier for the people in our new home to recognize us when we got there. The kids flew down the big dune right behind the bus, leaping like men on the moon.

When we took to the road again, I took us up the bigger highways, which were easier to negotiate in something that weighs five tons. We zoomed up the center of the state and before we knew it California was gone, a memory of succulent plants, dunes, rocks and the sea. We were in Oregon, home of the friendliest gas station attendants anywhere. But I missed the myth of California, which for me was real, and in Eugene we turned that big white bus around and flew back south. I am not kidding about how she hit her stride doing sixty-five down Highway 5 when she used to rattle along at fifty. We were meant to go back to the ocean, and we did.

I had surmised that neither Marin, nor Sonoma Counties were going to be the place to find my life, because the desirability/money equation was prohibitive, but Mendocino County was very desirable, nearly perfect for us, and not yet through the roof. So we drove through California's hot, crazy valley, then the gorgeous tawny-grass hills, the deep redwood glens, and came to the ocean at Navarro Beach. Point Arena was where I headed, because I wanted to get as far south as I could within the target area and because I used to subscribe to a magazine called Sage Woman, which is published there. The editorís byline always caught my eye, and every time I read it, I would wonder, why does she live there? I figured Iíd start by finding her and asking.

The rest is our little part of Point Arena history. My sons were in the brand new Pacific Community Charter School the day after we arrived. We camped in our schoolbus and they were driven to school in it, books falling, dishes clanging. We lived in that bus for a year. Soon after our arrival here, I flew back to Houston to get my car, so we could function in the American way. Our old house, where we left a lot of our things in the care of my ex-husband (the father of the oldest, who now lives out here, we are pleased to say), was suddenly condemned, looted and torn down. One could not ask for a clearer confirmation of oneís move.

I drove my little painted artcar back to California alone, with a whole lot of stuff, in four days. This was much harder than any bus drive, but my motivation was great. Two-thousand and one-hundred miles of flying pavement and I made it. We made it.

Now I own a house in this beloved town full of creative people and I have become, among other things, a waitress (after 18 years) and a politician, serving on the Point Arena City Council. What a long (fast), strange (good) trip itís been.

In

that time, I have not been back to Yellowknife. My obligations here, especially

working to pay for this comfortable home with its delightful old garden

and kitchen big enough to hold three tables, a couch and an easy chair,

do not permit much travel right now. But Tom informs me that the Thelon

mural has weathered badly and is peeling off its panels. The ground layer

seems not to be holding on to the paint. It looks terrible! What can I

do?

My

best idea is to paint it again, but here, so I can maintain all my other

stuff at the same time. And so people here, in my home area, can see it

before it goes. I will personally prime the panels and paint it in the

sun. The paint layers should be tough as a bone when itís done. Then we

can take it up north.

My good friend Jody Petty has stepped in with the offer of his nice, new king cab truck, a white champion steed big enough to fit us and three kids, with the mural panels on a rack on the top. So this time, my boys (and one of their friends) get to come with me. Weíll arrive at the height of the midnight sun and the mural will reappear, like a magical apparition arisen even brighter from its own ashes.

Thatís why this is a love story. Because I love that land. Because Tom loves the Thelon so much that he fights for it year after year. Because my beloved tundra gave me the inspiration to find my California home. Because I love THIS place so much and it and its people have been so loving to me that I can even contemplate the Thelon Mural Restoration Project.

So thanks for reading this and please spread the word. I will be painting the mural during the first weeks of June in downtown Point Arena, just north of the Arena Record building, with a reception planned for it on site, at 7 PM Wednesday, June 20th. Come say hi, consider me for bringing your artistic visions to life in your home or business, and if you feel so moved, contributions of any size to the Thelon Mural Restoration Project would be deeply appreciated!

The next one will be for Point Arena and our coastal world!

Lauren Sinnott ----May 29, 2001

July 29, 2001: The mural was painted in about nine days; we left on the summer solstice; and it's installed!

To order your

double-matted, archival quality 18"x13" print of the Thelon Mural II,

for $75.00 + $25.00 shipping and handling, link to my e-mail:

www.artgoddess.com

..............e-mail: lauren@artgoddess.com

Back to the main page

The Thelon Wildlife Sanctuary, NWT & Nunavut, Canada

Here are pictures of the new mural:

In progress, mounted on an historic building in Point Arena. The exterior grade 1/2" plywood panels were purchased locally, at S + B Hardware, in Manchester. Not only was S + B's everyday price on the panels exactly the same as at the two large building supply chains I called, but the owners further reduced the price to their cost as a favor to the project. Thanks to them!

Before mounting, the panels were primed in the highest grade Ace primer, chosen for me by Chuck at S + B. Thanks to Jim Hayes for his assistance in priming...

The sky was what I painted first--having learned my lesson that it governs the appearance of everything below it, plus if you start at the top, you don't have to worry about drips.

The last day,

in which I painted all the way from the wolves on the right, to the rocks

and lichen along the bottom, to the surface of the lake on the left and

underwater, where a Lake Trout swims in the deep blue! When this photo

was shot, guests were gathering for the opening reception and farewell

party.

|

|

|

|

Some words from Tundra Tom Faess, of Great Canadian Ecoventures:

The few places left on earth that are unaltered by men invariably seem hostile to him. One such place is the barrenlands of the remote Thelon valley of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, Canada. Few will ever see this strange land; lakes and rivers remain unnamed; animals roam without fear of man, plants exist undisturbed in a state of natural balance. Harsh winters dominate this remote northern country, sculpting the landscape at whim into graceful and delicate patterns. Duirng the brief Arctic summer, an abundance of activity, animal life and great peace prevails. Woven into the landscape is the vast sense of time unchanged - the secret mysteries of ancient cultures past…

The Thelon wildlife Sanctuary is one of the largest and most remote wild animal refuges in the world. Originally fueled by the advice of early Arctic explorers John Hornby and David Hanbury, the Thelon Sanctuary was established by Canada Order of Council in 1926. The original purpose was for the protection of musk oxen, whose populations had suffered dramatically from hunters who ventured off the European whaling ships during the late 1800's. However the sanctuary is significant for a variety of other reasons. This was confirmed when the International Biological Program (IBP) studies undertaken in the 1960's proclaimed the Thelon as an ecological site of universal importance. Wildlife within the sanctuary is provided legal protection by the prohibition of all hunting and trapping. The lands within this remote sanctuary are withdrawn from disposition to any person, and have been so since 1926. This has effectively prevented any disturbance from mineral prospecting and other development. It is now the only place in all of Canada that has such status, resulting with securing one of the only significantly complete unaltered ecosystems remaining in the world.

It is a little known geographical fact that the Thelon Valley, isolated by over 400 km. from the nearest road or settlement, is the most remote region on the North American continent, and possibly the world. The barrenlands, as they are locally called, offer a distinctly different than the tundra regions of the high Arctic or Alaska. The barrens lie in the vast Precambrian shield, a landscape of ancient bedrock-glaciated hills covered with a riot of lichens, wildflowers, and a variety of shrubs and dwarf trees. Between the stone hills, and just under the surface is permafrost, which prevents drainage and provides the setting for sedge and peat meadows.

Crisscrossing

over the countryside are esker systems: large sand and gravel hills deposited

by the receding glacier. As the Thelon is near the center of one of the

last great ice fields, the ancient striated Precambrian shield (3 billion

years old) and the recently deposited eskers (7000 years old) present an

astounding visible contrast of both the oldest and the most recent geology

on earth, side by side. The unique esker systems provide enough unfrozen

soil above the perma-frost for stands of white spruce and tamarack to take

root. These miniature forests grow far north of the recognized tree line,

forming an "oasis" of trees and other plants on the protected leeward slopes.

These trees in turn, provide shelter and roost for many animals and arctic

bird species. Scattered everywhere are signs of occupation by wolves; a

den hollowed out under the trees, well defined paw prints leading out in

every direction, bones and antlers that litter the hillsides all of which

provide a mini-museum for us to study.

|

|

It is the sandy loam of the eskers that make ideal den-digging conditions for tundra wolves, and create natural water crossings and highways for the migrating caribou of the Beverly herd. The unusual esker habitat is unique to the barrenlands and is the reason for the remarkable concentration of wildlife and birds found in the upper Thelon valley. Musk oxen have re-populated in the last few decades, and have spread out in all directions from the Thelon Wildlife Sanctuary. This remarkable mainland Arctic region is also home and roost to ptarmigan, Arctic & cross fox, sic sic's, black bear & barrens grizzly, Canadian & blue geese, old squaw and a variety of ducks in migratory flight preparatory stage. Like the surrounding vegetation, the esker oasis has an unusual mix of birds inherent both to the boreal forests and the arctic. The Thelon country is a major nesting and molting area for thousands of geese, sand hill cranes, and tundra swans. In the early autumn we will often have the chance to see them in the preparatory stage for their migratory flight south. Golden eagles; bald eagles plus a variety of hawks all have been known to nest in this region. The Thelon is considered by biologists to be one of the most significant nesting areas in Canada for rare peregrine and gyrfalcon. The upper Thelon region is part of the migratory route for the Beverly caribou herd. Recent estimates place them at 400,000 (+/-) animals - making the Beverly one of the largest and least influenced herds of the north. Their trails cover the seemingly unending landscape. . Musk oxen have re-populated in the last few decades, and have spread out in all directions from the Sanctuary.

In the 1970's, foreign mining conglomerates began exploration and drilling around the Thelon Sanctuary, primarily for uranium. Resulting from the tests, a mine was nearly developed near the Thelon by Baker Lake, NWT in the mid 1980's, however local protest from the Innuit peoples that live nearby put the project on hold for the time being. In the late 1980's, the barrenlands to the east of the Sanctuary became and still are a bustle of activity for the new riches discovered there - diamonds. Kimberlitic pipes containing gem-grade diamonds are being developed or are already in production. Companies such as De Beers and BHP Diamonds of Australia have multi- billion dollar mining developments already underway - the new North. The explorations have taken the companies eastward, and up along the Thelon Sanctuary boundaries. In recent years, the local and Federal governments began removing the Sanctuary from maps and publications. Closed-door negotiations have begun with the native bands in the area, and major payoffs are being played out. A new management plan for this previously highly protected and critical wildlife area may well leave an open door to mineral exploration and hunting. Concerned about the future of the Sanctuary, local Yellowknife wildlife guide Tom Faess contacted long time friend and artist Lauren Sinnott to come north and paint a mural at a key location in the capital city of Yellowknife, NWT. The mural was painted in 1998, and was strategically located to be right in the direct path of the political forces that will decide the sanctuaries fate - every morning people come face to face with the wonder of the Thelon depicted through Lauren's amazing mural on their way to work. Every day they are invited to reflect on the effect their decisions might have on this last true wilderness…

"Tundra

Tom" Faess--------May, 2001